In the summer of ’91, I dove headlong into training. I read all of the various bodybuilding magazines that I could get a hold of—or, at least, all of them that I could both afford and get a hold of. I was lucky, however, in that I had an off-again/on-again training partner who had stacks of magazines from around that time frame—primarily Ironman, Muscle and Fitness, and Flex—and I also had an uncle who had many older issue of Iron Manand Flex, plus things such as Strength and Health, and other such forgotten magazines that seemed (to me, at least) as if they were from another era.

Ironman had the most influence on me due to the “hardgainer” articles written by such writers as Steve Holman, Randal Strossen, Bradley Steiner, and Richard Winnett. All of these preached a “less-is-better” and “hard and heavy, but infrequent” training philosophies. (Not to say that Ironmanonly presented training philosophies from these sort of writers. They also included plenty of pieces from Gene Mozee and Greg Zulak, and neither one of those guys preached a “less is better” style of training, and in time both Zulak and Mozee had a much greater influence on my personal training philosophy in the mid to late ‘90s.)

|

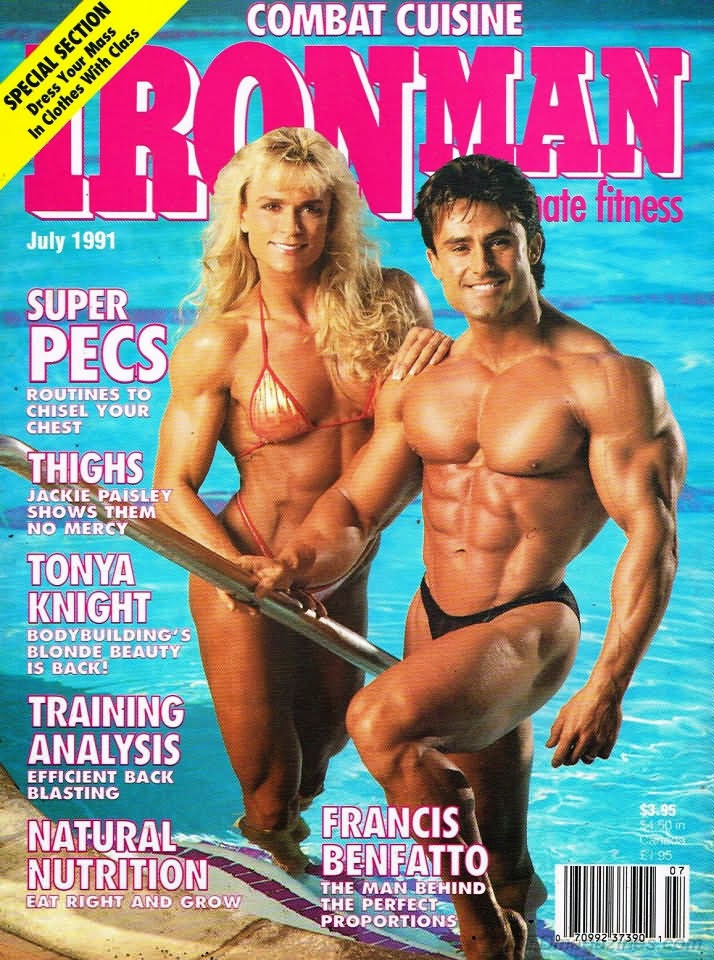

| The July, 1991 issue of Ironman |

Anyway, the gym where I trained also sold current issues of Ironman, and none of the others, which meant that I spent hours sometimes sitting in the lobby reading them either before or after a workout. In June of ’91 (I remember it decidedly), I picked up the July, 1991 issue of Ironman and discovered—what seemed to me at the time—the oddest form of training: double-split workouts. The article in particular was one about the training of Francis Benfatto, he of the almost Greek god-like physique. Benfatto used a style of double-split training where he would train a muscle group twice in the same day. The early workout would typically use just one exercise for the particular muscle groups of the day, working on density and muscle mass, and the second, later, workout would consist of multiple exercises for the same muscle group, working on “shaping” a muscle.

I quickly dismissed such a form of training. After all, or so I reasoned, that kind of training was only for “genetically gifted” and “chemically enhanced” bodybuilders.

In case you haven’t already surmised it, I don’t exactly feel that way any more. Not that I would recommend a style of training exactly like Benfatto’s, but I do think that double-split training can be quite effective if used properly[1].

Starting Off

This first program is for those of you who would like to do a double-split workout, but have never done a high-volume program. However, I would recommend at least a couple months training on a 3-days-per-week, full-body workout before attempting this one.

For this program, both workouts of the day will involve only two exercises each. Technically, yes, you could quite easily do both workouts as one workout, but you will gain more muscle at a faster rate if you don’t do this. Using two workouts on each training day allows you to recover faster and take advantage of peri-workout nutrition, not to mention the fact that it allows you to have two more intense, focused workouts.

Day One

Workout One:

- Squats: 5 sets of 3 reps. After warm-ups, use approximately 80% of your one-rep max for all 5 “work” sets of 3 reps.

- Bench Presses: 5 sets of 3 reps. Same set/rep scheme as the squats.

Workout Two:

- Walking Lunges: 4 sets of 10 reps, each leg. After warming up for a few sets, use approximately 70% of your one-rep max (with either dumbbells or a barbell) for all 4 work sets of 10 reps. These sets should be tougher than the squats earlier.

- Incline Dumbbell Presses: 4 sets of 10 reps

Day Two

Workout One:

- Barbell Overhead Presses: 5 sets of 3 reps

- Barbell Curls: 5 sets of 3 reps

Workout Two:

- Seated Dumbbell Presses: 4 sets of 10 reps

- Dumbbell Curls: 4 sets of 10 reps (each arm)

Day Three: Off

Day Four

Workout One:

- Deadlifts: 5 sets of 3 reps

- Power Cleans: 5 sets of 3 reps

Workout Two:

- Stiff-Legged Deadlifts: 4 sets of 10 reps

- Dumbbell Rows: 4 sets of 10 reps (each arm)

Day Five: Repeat Day One workout, but take off on day 6 before starting a 2 on, one off/ 2 on, one off cycle again

After about three weeks of training, change over to some different exercises and/or some different rep ranges. On the heavy workouts, change over to either 5 sets of 2 at 90% or 5 sets of 6 at 70%. Conversely, on the lighter workouts, perform some heavier work at 4 sets of 8 reps, or some lighter days at 3 sets of 15 reps.

In Part Two, we’ll take a look at some advanced workouts for those of you brave enough to try them.

[1] I will be honest, here. I don’t think this training is practical for those of you who train at a commercial gym, unless you feel like traveling there twice each day. It’s suited more for those of us who have a home gym, or for those of you who want to perform one workout at a commercial gym, and the second one at the house.